Ten years ago Beijing's parking problems were among the most extreme I had ever seen.

Surprisingly, it is much much better now, as I learned from "How Beijing Is Rethinking Parking and Reclaiming Public Space", an article by Liu Shaokun and Bram van Ooijen in the Nov. 2022 edition of Sustainable Transportation Magazine from the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy (ITDP).

Beijing still has much to do, but it is an encouraging story! So I reached out to Shaokun and Bram, as well as

Shaokun's colleague Huang Yangwen, for this month's Reinventing Parking podcast.

Listen with the player below. Or subscribe to the audio podcast. This is the official podcast of the Parking Reform Network.

Reinventing Parking is the official podcast of the Parking Reform Network. Visit the PRN website or follow PRN on social media to catch up.

Below are highlights from our conversation about Beijing parking reform

|

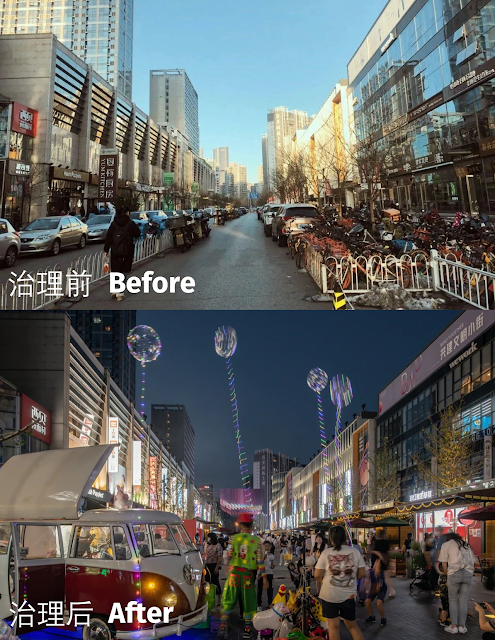

| Conditions in Beijing have improved greatly for people on foot or bicycle. Wangjin Xiaojie (image by ITDP China) |

My three guests this time were:

Liu Shaokun is the Vice Country Director of ITDP China, where he has worked on sustainable transport since about 2009.

Huang Yangwen is a young transportation engineer in ITDP's Guangzhou office

and has worked on sustainable transport projects in cities such as

Guangzhou, Jinan and Tblisi in Georgia.

Bram van Ooijen was with ITDP China from 2010 to 2015 and since then he has been based in China as an urban transport consultant with experiences in cities across Asia, Africa, and South America.

Beijing's awful parking situation by 2012 and its genesis [3:20]

China's economy has been growing rapidly for decades and the big cities motorized rapidly between about 1999 and 2011. This quickly led to traffic and parking problems but we will see that Beijing has also been finding ways to work itself out of that trouble.

The authorities tried to expand roads and parking to keep up. But there was no way to expand parking capacity fast enough. Bram described the situation by 2012 or so:

"Wherever there was a space available, people would park. Footpaths and setbacks would be full of parking. There was no more space to walk on the footpath so people walked on the street. Bike lanes no longer were bike lanes because people were parking there. Buses couldn't stop at the bus stops because people would park there. Little parks and public spaces would be taken over by parking. So literally there was parking everywhere. That impacted not only pedestrians and cyclists and bus users, but also traffic itself. Roads got blocked by illegal parking. Traffic was circling just to find space. This wasn't working for anyone."

Even inside most residential compounds there was chaos, especially in those built before about 1995 with little or no parking. Recreation space was paved over for parking.

Yet non-residential off-street parking was mostly empty! [7:12]

Despite all this chaos, parking shortage was not the problem in many areas.

In 2014, ITDP looked at a number of typical districts with overburdened on-street parking and found that off-street public parking massively under-utilized.

|

| An illustration from ITDP China's 2015 Parking Guidebook for Beijing |

It is the same story that we see in so many cities. Free or under-priced on-street parking was full while priced off-street parking had plenty of empty spaces.

A dysfunctional on-street pricing system [9:00]

In fact, many Beijing streets did have paid on-street parking with fees set by the government with the aim of steering demand towards that empty off-street parking. But the actual practice on the street was not as intended.

Fee collection was via private concession: companies paid a certain fee to the government for the right to

operate. This had numerous problems. They would often operate more spaces than the official ones, including sometimes even on the footpath. Fee collection was not consistent and many parked for free or for less than the official rates. There was little or no enforcement. And cash payments to attendants made it easy for attendants and companies to under-declare their revenue.

City officials knew that a better system was needed but were reluctant to anger motorists.

How did change arrive? [11:05]

Shaokun highlighted that chronic air pollution problems in the 2000s made the public hungry for solutions.Action on parking and on Beijing's wider transport problems came in the context of new national leadership and stronger action on environmental problems.

The government was also more willing than before to risk upsetting stakeholders, such as Beijing's motorists.

Parking reform, when it came, was spearheaded by improved pricing arrangements and stricter enforcement. There was some unhappiness from motorists but protest was allayed through strong public communication efforts and by a strategy of phasing in many of the changes area by area and over several years.

Car ownership growth slowed after the License Plate Lottery began in 2011

Before the parking problems were tackled head on, the pace of

motorization was drastically slowed. This helped slow the growth of

Beijing's car-related problems and bought time to enact solutions.

Shanghai had been slowing the rate of car ownership increases for many years via a license plate auction system. And Beijing had tried various mild efforts to slow vehicle growth before 2011.

But in 2011 the city took decisive action by limiting the number of new motor vehicle licenses allowed each year but used a lottery rather than an auction as the rationing method. Only about 100,000 new vehicles can be licensed each year in Beijing.

Improved mobility options also helped [15:00]

Such policies and the later parking efforts were also made more palatable by drastic improvements to other transportation options since 2010 or so. For example, since 2012 eleven metro lines have opened, adding 341 kilometers to the already large network. Bus services have also improved.

Bram also pointed out the rise of bicycle sharing, as an option for short trips and to get to and from public transport.

Step by step towards better parking policy from 2016 or so [17:05]

Parking management improvements accelerated in 2016 with a series of steps: - improved ("smart") on-street pricing

- improved enforcement (step by step)

- a communication campaign to explain why this is necessary.

The city government took back all of the private on-street parking fee concessions and implemented its own system, with payments via a phone app. This enables rich collection of parking data to inform the parking management and enforcement.

Cameras help with the improved enforcement

Improved enforcement has resulted in much less tolerance for illegal parking than before.

This enforcement is efficiently carried out with the help of both fixed cameras and cameras on mobile enforcement vehicles (both e-bikes and cars).

The authorities were nervous about a backlash if enforcement became too strict too suddenly. So stricter enforcement has been expanding road by road and area by area.

|

| Weijiacun nanlu (Image by ITDP China) |

On-street parking can only be conveniently paid for by phone [20:30 and 23:00]

As mentioned above, payment for on-street parking is by phone app. This is the most convenient method.

However, if a motorist can't pay by phone for some reason, they do have the option of going to an authorized offline payment channels to pay. These include outlets of the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, China Merchants Banks, Agricultural Bank of China.

These options seem to be rarely used. Phone based payments are almost universal now in China and no one thinks it odd or harsh for this to be the only convenient option.

An interesting residential permit system [24:30]

Residential permits are now available in residential streets that lack enough off-street parking.

Around the world, most residential on-street parking permit systems involve a flat fee paid on a per-month or per-year basis.

In Beijing, residential permit holders have two payment options. They can choose to pay by the month OR by the hour.

The price of parking charges in each community is not exactly the same, but the charge cannot be higher than the night charge for on-street parking. That is, it is usually not higher than 1 yuan/2 hours, so the monthly subscription price designed by some communities is 360 yuan/month, which means that the monthly subscription actually pays the parking fee for 30 days a month and 24 hours a day.

That monthly fee of 360 Yuan is about USD52.

Deregulated prices for privately-owned parking [26:45]

Beijing has also abandoned its previous policy of controlling the prices of private-sector off-street parking. The owners of parking are now free to charge what the market will bear.

Previously, in Beijing and many other Chinese cities, privately owned parking that is open to the public faced strict price controls overseen by price bureaus.Street design efforts were a large part of the parking success and have greatly improved conditions for people on foot or bicycle [27:00]

Improved on-street parking in Beijing is not just the result of improved pricing and enforcement.

Beijing has also improved the design of streets and their on-street parking arrangements. This has been done as part of huge efforts to make public transport, walking and cycling more attractive.

After years of being blocked by parked vehicles, high quality bikeways are again a common feature of Beijing's roads.And bollards are very widely deployed to make sure that vehicles can't drive or park on sidewalks.

Recent data shows that bicycle use is indeed increasing again in Beijing.

|

| Niujie Sitiao (Image by ITDP China) |

Policy shifts on parking standards (parking mandates) [28:45]

After decades of applying only minimum parking requirements (parking mandates) and gradually increasing their levels, Beijing shifted to a new approach in 2020.

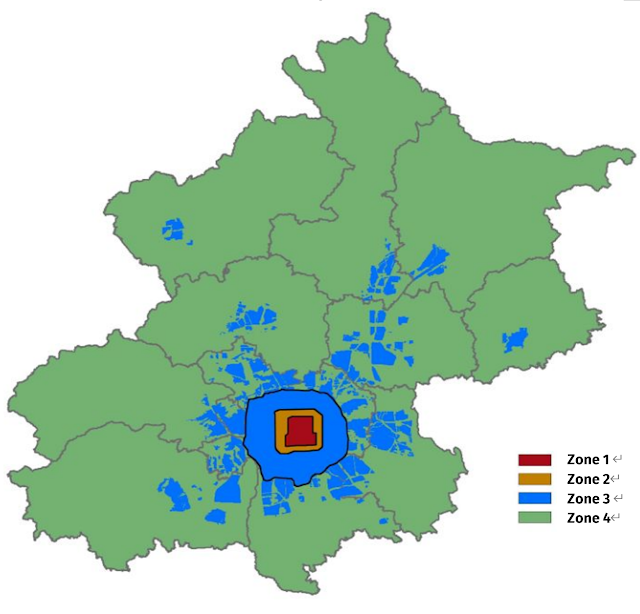

Parking minimums were abolished in the central area within the second ring road (zone 1 below). That area now has only parking maximums.

Most of the populated parts of the city (zones 2 and 3 below) now have both parking minimums and maximums.

Zone 2 is the area between the second ring road and the third ring road. Zone 3 is the area between the third ring road and the fifth ring road, plus other areas, the black line is the fifth ring road

Only a far outer zone (zone 4 below) still has only minimums.

Similar reforms to parking standards have been enacted in China's other megacities and Shaokun believes other cities across China will gradually follow their lead.

|

| Beijing's parking standards zones (Image via ITDP China) |

Residents can "share" parking in office buildings (for example) [31:00]

Many Beijing districts have systems to enable residents of buildings and streets that are short of parking to rent overnight parking within the compounds of nearby non-residential buildings.

Government office buildings are especially common participants in this.

Beijing's parking situation is visibly much improved [33:30]

It may be too soon for data to corroborate our impressions of a much improved parking situation in Beijing.

But my guests were clear that the change is very obvious in the streets with much less illegal parking and easier parking availability for motorists.

|

| Wangfujin (Image by ITDP China) |

This summary was prepared with help from a transcription by Descript.

IF YOU LIKED THIS

Subscribe, if you haven't already (it's free):

- sign up to get Reinventing Parking updates by email

OR - subscribe

to the audio podcast (search for 'Reinventing Parking' in your podcast

player app or click the symbol that looks like a wifi icon in one of the

players at the top or bottom of this article

Comments

Post a Comment