I am a great fan of Dr Liz Taylor's research on parking so it was wonderful to interview her recently.

We had a long discussion, much of which will be included in future Reinventing Parking episodes on various topics.

But for this edition I chose a selection of segments that are mostly about the collision between parking reform and anti-development sentiment in residential areas. I think you will find Liz's insights on this both important and entertaining.

Listen with the player below. Or subscribe to the audio podcast. This is the official podcast of the Parking Reform Network.

Reinventing Parking is the official podcast of the Parking Reform Network. Visit the PRN website or follow PRN on social media to catch up.

Liz Taylor is a senior lecturer in Urban Planning and Design at Monash University in Melbourne.

The research papers that are mentioned or relevant to this episode are:

Below is a lightly edited transcript of the episode.

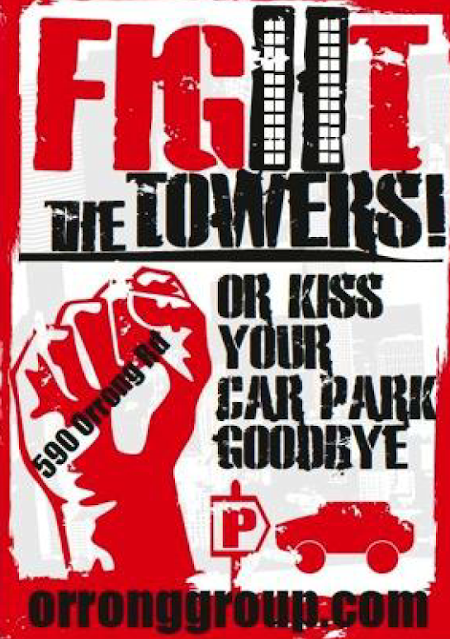

“Fight the towers! Or kiss your car park goodbye”

Paul: You have a talent for entertaining names for your papers, and the paper that got you interested was "Fight the Towers or Kiss Your Car Park Goodbye", which I gather was a quote from a flyer in Melbourne.

A lot of the inner parts of Melbourne have had increasing construction of apartments. And of course the neighbors don't always like it.

In this case, the neighbors in Toorak, which is a well-heeled suburb of Melbourne, had put together a poster to mobilize community opposition to the construction of towers, which I think it is important to note, were literally next to the train station.

|

| Here are the "towers" that were built despite the campaign mentioned above. |

'Fight the Towers or Kiss Your Car Park Goodbye' - that equivalence, which I still see now, that any increase in housing is an increase in cars, and specifically that any increase in cars is a direct threat to your own cars occupation of public street space, was definitely the way I found my way into this.

It's been incredibly contested for years. It's around change and anxiety about people arriving and population increases. But it's also the fact that population increases have meant increases in cars. The growth in car ownership and car use in Melbourne has far outstripped growth in dwellings or population. So people do have that experience of cars in Melbourne.

You can't actually submit a planning objection to people buying a car, but you can object to apartments going up next door.

That's the sort of equivalence that people feel. And there's also, I think, a desperate belief that if you can just stop the apartments being built, that you'll be able to park your car at the front wherever you go. I found it really frustrating.

And in that original paper, Fight the Towers or Kiss Your Car Park Goodbye, I ended up thinking about it in terms of rights. That was actually, I think through one of the reviewer comments. So, whoever they were, Thank you! I was thinking about the assertion of rights and rights, the space and the ways cars figure into that.

Rights perspective and equity issues around parking

Paul: That's been a theme that you've explored in various contexts, hasn't it? And it's a very interesting way of looking at it, because it's bizarre, isn't it? Machines, cars, having rights somehow.

Liz: Yeah, but deep deeply politicized rights. A right to the city.

And where it gets, I think challenging for me and also interesting is that for many people they do experience the world through a car.

Often you're talking about a diversity of experiences. People with a disability, women who are afraid of violence or who experience violence. I've been thinking lately about people who have experienced homelessness. In a context in which housing is extraordinarily expensive, a car is often the closest version of a house that people have.

So there is something genuine about the car's right to the city being a person's right to the city.

But then I also just wanna wheel it back and say, no, they're a car!

And, not only are they an object, they're a lot larger than a person. So accommodating them is difficult.

And then the consequence part that I landed on with that initial paper was the consequence of this assertion of rights and the right to park on the street. It impacts other people's rights in the sense that those that are buying the apartments or renting the apartments, they have to have this parking that they don't even use.

And the planning system, which is supposed to be considering all kinds of environmental and economic considerations in terms of land use spends most of its time thinking about parking and is under pressure to just have more parking.

Paul: A huge amount of human resources in the planning system is devoted to something that could be dealt with so much more easily.

In fact, all of those equity issues can and should be addressed. And it's certainly true that there will be car dependent individuals in need, and we need to find a way to accommodate their needs. But giving everybody free parking in the name of, helping those particular people doesn't seem efficient.

Liz: These things really genuinely matter.

As you say, planners should care, anyone with an interest in public space should care about whether someone can afford to access space, someone feels safe in space, etc. But parking is not the thing that's gonna solve that.

And there's something also deeply suspicious about the fact that suddenly everyone cares about whether or not a nurse can afford to get to work because it's something to do with free parking. They didn't care about it when it came to affordable housing, or better public transport, or better pay. Any of these things that led to this woman having to pay for parking all mattered and we can't solve it just by making her parking free. She's probably spending - this imaginary person - two thirds of income on the car.

Paul: I think in that same paper, you had a nice paragraph where you had a juxtaposition between the what-if fears around small shortages of parking and the shocking fact that it might then need to be managed versus the what-if scenarios around all sorts of far more important planning issues that the planning system says are its top priorities like climate and local drainage and all sorts of other very important things... housing!

Liz: Yes, housing, trees, all sorts of considerations of life and urban space. But parking is that kind of Trump card.

And that's why I've continued to study it. But I also have moments of being like, I don't know.

Confusion over parking reform

Paul: With a lot of the anxiety around abolishing minimums, you get the impression that many people are a bit confused. In their minds they're thinking maximums and that there will not be enough parking fears. Those might be reasonable, if we were talking about maximums,

Liz: Yes, there's confusion. And that's how I got interested in it.

When you do a development [in Melbourne], you have to put up advertising. And the advertising won't say how many parking spaces you have. It'll say whether you're looking to reduce it from the mandated number.

And most people seem to interpret that in two key areas of anxiety. One is that it sounds to them as though someone's literally coming along and taking away car parking spaces rather than reduction in the minimum additional number of car parks that you're gonna put in.

And secondly, they just think about the on street parking. That's a continuous point of frustration for me that it's so hard (outside of the world of parking reform nerds) to think about off-street parking and on street parking in the same conversation.

People parking on the street are clearly doing it all the time, because they're the ones worrying about it!

They're worried that, if a new development doesn't have enough off street parking, someone's going to park on the street and THEY won't be able to park on the street. So they make the new development have more parking.

I think it's driven me crazy at times. Like, do you really think that adding a hundred car parks in that apartment building is gonna mean you can park on the street?

There's also something procedural. The burden of proof. You have to start with the minimums and any alternatives have to defend themselves. At least that's the kind of situation outside of the Central Business District.

Who's Been Parking in My Street? Who actually parks in the streets in residential areas?

Paul: We started off talking about residential developments and the opposition to those, using parking as an excuse. There's an element of using parking as an excuse and an element of real fears about where will I park? It's hard to say exactly which is more important.

Liz: I've tried to find out but it's just me.

Paul: But you did some research to investigate who really was parking and why were there problems in certain areas.

Liz: In residential areas? Yeah. I think I originally had a punny title and then by the time I got into the journal, I changed it to a normal title ...

Paul: Who's been parking on my street!

Liz: That is a punny title. I think it's later published as just Politics of Residential Parking. And that was meant to be a reference to The Three Bears or something.

The motivation for that was coming out of my initial interest in parking being around densification in new housing construction in Melbourne.

A lot of the planning systems attention and certainly a lot of the public engagement and opposition to change is around parking, and specifically the fear that if you build apartments, people will park on the street and that will mean that other people can't park on the street anymore.

And therefore either ... I think the preferred version is no apartments... but if we do build new apartments, they have to meet the minimum requirements. Or preferably exceed them. The more parking the better. That was the situation.

But then I was thinking, it's not ever actually been established who is parking on the street in residential areas in these Australian cities where it's such an increasingly contested space of the street in residential areas. Who is actually parking on it? Is it people in apartments? And is it because they don't have enough parking required or provided?

There wasn't any evidence about that at all. So I wanted to try and understand that.

I made use of, two imperfect sources. One is this ongoing travel survey they have in Victoria called VISTA, the Victorian Integrated Survey of Travel Activity. It's like a travel diary system and that had some data in there around how people traveled of where they parked and how they paid for it at the end of the journey. And I also put out my own online survey for people. It was voluntary, which comes with its own limitations. I asked about how much parking do you have and where do you park at home essentially.

My initial suspicion was that the reason people would park on the street in a residential area was they just had too many cars. That's where I was coming from. But it ended up slightly surprising and it's been a useful insight for me.

I found that the most common users of street parking in Australian cities are people in detached houses and to a lesser extent terrace houses, townhouses.

So not apartments. The apartments are the minority of housing anyway, but they use less of the street parking than the proportion of housing stock they make up. So it's mostly people in lower density housing using the street parking by a fairly large margin.

And then secondly, something around a third or 40% of people in apartments have parking spaces that they don't use at all. They don't have a car but they can't use it for anything else, which is quite a confronting fact in some ways.

So why is it that people that park on the street at home are fighting it out constantly for street parking?

I found that most of them ... not all of them, but the majority of them ... had parking. Specifically, they had garage parking but they were using their garage to store, store their stuff.

That finding tied into a few interesting papers since that, which I have been great to see.

Paul: Los Angeles and other places with similar findings.

Liz: I think one from somewhere else in California recently. And certainly one from Germany as well.

So it's not necessarily a supply question for parking. It's how you choose to park and that word rights again.

So in this Australian context, they have a garage, but they just fill it with all their stuff and then they park on the street cuz they can.

Then they try to make someone else have a car park! A car park which they may not need.

Unused parking in apartments in Australia usually can't be used for anything else or even rented to anyone else

Liz: And in fact that they can't use.

There's a legal difference around apartment parking (usually basement or multi-level parking) in what we call strata housing here with an owners corporation.

The car park is controlled by another level of governance called an owners corporation or a strata. And they usually restrict your use of that space.

So I had people in my survey talking about how they live in an apartment, they have a car parking space, they don't have a car, they can't use it for anything else because of the owners corporation rules.

Even renting it to anyone else seems to be very difficult.

When I'm feeling more motivated that's an area I think of parking reform or change in Australia, I think has a lot of possibility.

We've built a lot of residential parking in particular that isn't actually used very much and it could be brought into broader circulation. It could ease some of that pressure on the street parking.

It shouldn't be difficult but it is in practice because of the owners corporation rules around security and things like that.

Elephant in the Planning Scheme: a long view of parking in planning in Melbourne

Paul: Another one of your papers was the "elephant in the planning scheme"Liz: That's the historical one looking at the long history since the 1920s in Melbourne of how parking has been managed.

In Donald Shoup and others' parking work, I think you inevitably have to look historically. If you just zoomed in from outer space now, you wouldn't go, what we need to do is put in a lot of parking.

So to understand why things are done the way they are, I think you have to look back. It is part of the history of automobility and how cities are planned around and shaped reshaped by [cars]. In this case I looked specifically at Melbourne.

How have planners thought about parking, what was their attitude to solving parking problems and how is this reflected in legislation as well? And I was mainly interested in just tracing the history of where did this come from?

The main points of interest I got from it was that, first of all, the very first metropolitan plan was a plan prepared for Melbourne in 1929. It was never implemented but it was a very comprehensive set of ideas and surveys.

And it is a kind of classic arc of motorization where the city is starting to be like swamped by cars and there are cars everywhere. And that document is really interesting because it talks about cars and car parking, sort of the same way Parking Reform Network would. It's like they're everywhere and they just take up space.

Planners at that point in Melbourne were very much putting forward an idea that actually these new cars shouldn't have such an unmitigated claim to public space and we need to do something about it.

But that never came to pass. By the time town planning legislation was actually really given teeth and the strategy was implemented, it was in the post second World War period, when motorization had really escalated, car ownership was much more rapidly taken up.

And the planning scheme at that point, very unapologetically proposed how can we make Melbourne a place that's easier for parking, marrying up in a way the strategy, which was to make the city more amenable for parking, with the minimums, which they copied.

They very directly got the parking minimums from Los Angeles. Charles Banner, who was the head of planning for Los Angeles, was invited out to talk about how planning and zoning work and parking. Parking minimums were adopted Melbourne-wide on the strength of that Los Angeles connection.

IF YOU LIKED THIS

Subscribe, if you haven't already (it's free):

- sign up to get Reinventing Parking updates by email

OR - subscribe

to the audio podcast (search for 'Reinventing Parking' in your podcast

player app or click the symbol that looks like a wifi icon in one of the

players at the top or bottom of this article

Comments

Post a Comment